Skyward -- Trinity

May 2019

As the world prepared for war in 1939, a group of physicists was studying how to reproduce the behavior of a star on Earth: to split an atom, either quietly to provide a virtually unlimited source of power, or explosively to create a weapon of mass destruction. Worried that the Gemans might develop an atomic bomb first, astrophysicist Leo Szilard wrote a letter to President Roosevelt suggesting that the Americans should develop the bomb first. Thinking that the letter would have more impact if it were signed by the foremost scientist of that time, Szilard made two visits to Albert Einstein’s summer home in Cutchogue, on Long Island, New York. They persuaded him to sign the letter.

As the world prepared for war in 1939, a group of physicists was studying how to reproduce the behavior of a star on Earth: to split an atom, either quietly to provide a virtually unlimited source of power, or explosively to create a weapon of mass destruction. Worried that the Gemans might develop an atomic bomb first, astrophysicist Leo Szilard wrote a letter to President Roosevelt suggesting that the Americans should develop the bomb first. Thinking that the letter would have more impact if it were signed by the foremost scientist of that time, Szilard made two visits to Albert Einstein’s summer home in Cutchogue, on Long Island, New York. They persuaded him to sign the letter.

Einstein’s letter had an immediate and powerful impact on Roosevelt. He immediately set in place the  initial research that led to the start of the Manhattan project in June of 1942. Within three years, the first plutonium nuclear device was test detonated near Socorro, New Mexico in the Jornada del Muerto (ironically translated to Dead Man’s Journey) desert. J. Robert Oppenheimer named the actual test site Trinity, after the first lines in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14:

initial research that led to the start of the Manhattan project in June of 1942. Within three years, the first plutonium nuclear device was test detonated near Socorro, New Mexico in the Jornada del Muerto (ironically translated to Dead Man’s Journey) desert. J. Robert Oppenheimer named the actual test site Trinity, after the first lines in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14:

Batter my heart, three-person'd God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

On July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 am, the nuclear device detonated and the atomic age began. Just one month later, two bombs were exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, and the Second World War came to a sudden end.

It is now 73 years later. On April 6 our daughter Nannette, son-in-law Mark, grandson Matthew, friend David Rossetter, and Wendee and I visited Trinity Site. It was a special and emotional experience for us. We felt the shudder and silence of those who witnessed the blinding flash of light that turned dawn into noon across that lonely desert. The power and force of the detontion reinforced the feeling of scientists there that this weapon was not a joke. It was used in combat twice, and it is now a part of history. We visited that day to expeience the effect on people who felt the shock wave from 160 miles away and who had to replace broken windows in Albuquerque, where our family lives today. We didn’t see much trinitite there, as the army did an excellent job removing the radioactive glass. We did not get much exposure to radiation either; accoding to Army statistics, our one hour visit to Ground zero gave us at most one millrem of radiation exposure, compared to an average annual dose of 620 millrems from medical and natural sources.

It is now 73 years later. On April 6 our daughter Nannette, son-in-law Mark, grandson Matthew, friend David Rossetter, and Wendee and I visited Trinity Site. It was a special and emotional experience for us. We felt the shudder and silence of those who witnessed the blinding flash of light that turned dawn into noon across that lonely desert. The power and force of the detontion reinforced the feeling of scientists there that this weapon was not a joke. It was used in combat twice, and it is now a part of history. We visited that day to expeience the effect on people who felt the shock wave from 160 miles away and who had to replace broken windows in Albuquerque, where our family lives today. We didn’t see much trinitite there, as the army did an excellent job removing the radioactive glass. We did not get much exposure to radiation either; accoding to Army statistics, our one hour visit to Ground zero gave us at most one millrem of radiation exposure, compared to an average annual dose of 620 millrems from medical and natural sources.

As we left the site we passed a protest going on at the entrance. After all these decades, what happened that rainy July day in 1945 still has a profound effect on the people who lived and live in the atomic age. For a second that day, humanity witnessed the process of a star here on Earth. And when I got home that night and looked up at the peaceful stars, I shuddered again.

Picture 1: Inscription on the obelisk at Ground zero.

Picture 2: remains of a footing from the tower that supported the bomb and which was incinerated that day.

Picture 3: The Schmidt-McDonald house, where the bomb was assembled. All photographs were taken by David Levy.

This month we're fortunate to have Catherine Zucker of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics as our guest speaker. Catherine will show us how we have begun to derive accurate distance measurements to large, star-forming molecular clouds in the Milky Way galaxy, and what that means for astronomy.

This month we're fortunate to have Catherine Zucker of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics as our guest speaker. Catherine will show us how we have begun to derive accurate distance measurements to large, star-forming molecular clouds in the Milky Way galaxy, and what that means for astronomy.

Our speaker for the Friday, June 14 GAAC meeting will be none other than Steve O'Meara, the amateur astronomer who, very unexpectedly, observed "spokes" in Saturn's ring system in 1976. Steve reported observing these phenomena with the 9 inch refractor at Harvard (an interesting account of the reception of O'Meara's observations is available

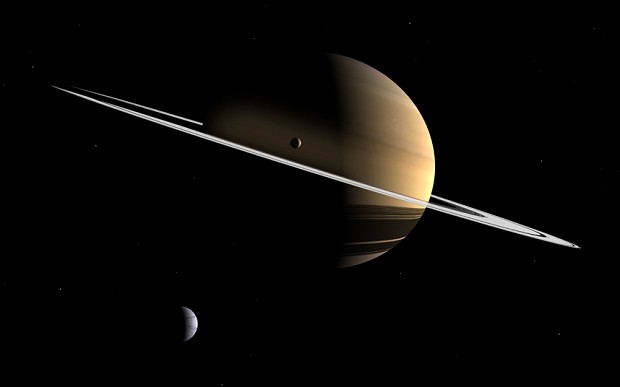

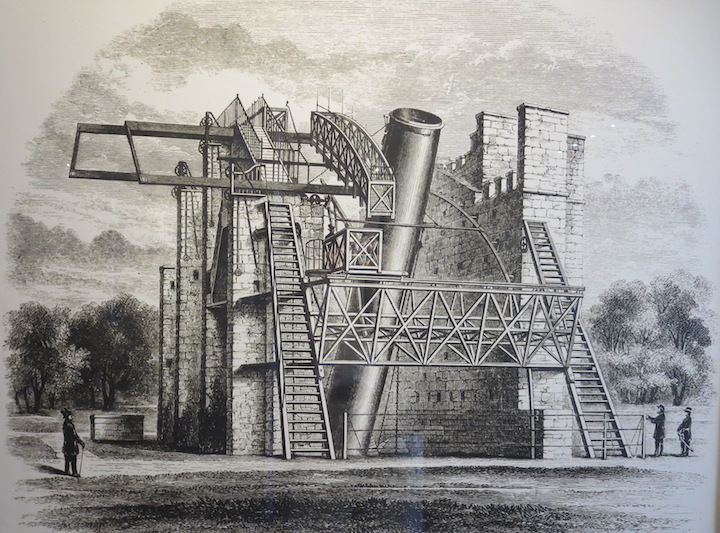

Our speaker for the Friday, June 14 GAAC meeting will be none other than Steve O'Meara, the amateur astronomer who, very unexpectedly, observed "spokes" in Saturn's ring system in 1976. Steve reported observing these phenomena with the 9 inch refractor at Harvard (an interesting account of the reception of O'Meara's observations is available  At our May 10 meeting, Amateur astronomer and perennial GAAC favorite Dwight Lanpher will speak about his visit last September to Birr Castle, County Offaly, Ireland to examine "the Great Telescope." Any review of the history of astronomy will likely discover this large telescope called the "Leviathan of Parsonsonstown." Built in Ireland in 1845 by the 3rd Earl of Rosse, it was the largest telescope in the world for 70 years. Each of two 72" speculum-metal mirrors were alternately mounted in a 54' long tube, suspended between two purpose built castle walls.

At our May 10 meeting, Amateur astronomer and perennial GAAC favorite Dwight Lanpher will speak about his visit last September to Birr Castle, County Offaly, Ireland to examine "the Great Telescope." Any review of the history of astronomy will likely discover this large telescope called the "Leviathan of Parsonsonstown." Built in Ireland in 1845 by the 3rd Earl of Rosse, it was the largest telescope in the world for 70 years. Each of two 72" speculum-metal mirrors were alternately mounted in a 54' long tube, suspended between two purpose built castle walls. During our monthly star nights at our neighborhood Corona Foothills Middle School, I sit down on a chair near the telescope to assist with the observing. The students attending are well behaved no matter their level of interest. Some of the kids are there just for the evening’s assignment. But occasionally one student or two will sit down next to me and ask me a few questions.

During our monthly star nights at our neighborhood Corona Foothills Middle School, I sit down on a chair near the telescope to assist with the observing. The students attending are well behaved no matter their level of interest. Some of the kids are there just for the evening’s assignment. But occasionally one student or two will sit down next to me and ask me a few questions.  But I had to wait a while before I saw my first comet. I was already 17 years old and had been interested in the sky for a number of years. When I learned that the two young Japanese amateur astronomers Kaoru Ikeya and Tsutomu Seki had discovered a comet that could become the comet of the century, I was spellbound. During the mild autumn of 1965, as I awaited this mighty comet, I decided to begin a comet search program of my own.

But I had to wait a while before I saw my first comet. I was already 17 years old and had been interested in the sky for a number of years. When I learned that the two young Japanese amateur astronomers Kaoru Ikeya and Tsutomu Seki had discovered a comet that could become the comet of the century, I was spellbound. During the mild autumn of 1965, as I awaited this mighty comet, I decided to begin a comet search program of my own.

This month we're pleased to have as our speaker Sarah Blunt from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Sarah's presentation is titled "Know thy Star, Know thy Exoplanet."

This month we're pleased to have as our speaker Sarah Blunt from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Sarah's presentation is titled "Know thy Star, Know thy Exoplanet."