Is there a super-Earth in the Solar System out beyond Neptune?

By Ethan Siegel

When the advent of large telescopes brought us the discoveries of Uranus and then Neptune, they also brought the great hope of a Solar System even richer in terms of large, massive worlds. While the asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt were each found to possess a large number of substantial icy-and-rocky worlds, none of them approached even Earth in size or mass, much less the true giant worlds. Meanwhile, all-sky infrared surveys, sensitive to red dwarfs, brown dwarfs and Jupiter-mass gas giants, were unable to detect anything new that was closer than Proxima Centauri. At the same time, Kepler taught us that super-Earths, planets between Earth and Neptune in size, were the galaxy's most common, despite our Solar System having none.

When the advent of large telescopes brought us the discoveries of Uranus and then Neptune, they also brought the great hope of a Solar System even richer in terms of large, massive worlds. While the asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt were each found to possess a large number of substantial icy-and-rocky worlds, none of them approached even Earth in size or mass, much less the true giant worlds. Meanwhile, all-sky infrared surveys, sensitive to red dwarfs, brown dwarfs and Jupiter-mass gas giants, were unable to detect anything new that was closer than Proxima Centauri. At the same time, Kepler taught us that super-Earths, planets between Earth and Neptune in size, were the galaxy's most common, despite our Solar System having none.

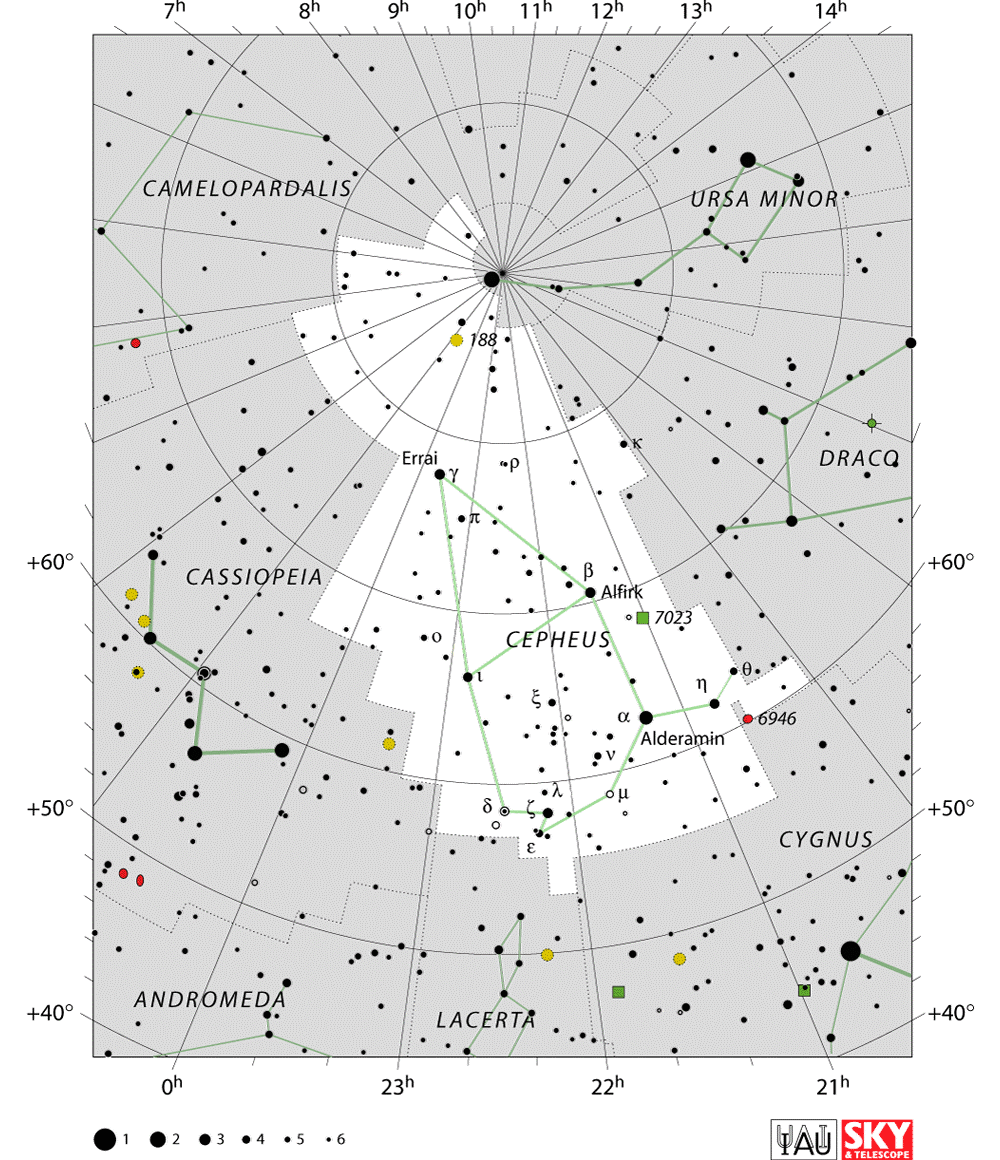

The discovery of Sedna in 2003 turned out to be even more groundbreaking than astronomers realized. Although many Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) were discovered beginning in the 1990s, Sedna had properties all the others didn't. With an extremely eccentric orbit and an aphelion taking it farther from the Sun than any other world known at the time, it represented our first glimpse of the hypothetical Oort cloud: a spherical distribution of bodies ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands of A.U. from the Sun. Since the discovery of Sedna, five other long-period, very eccentric TNOs were found prior to 2016 as well. While you'd expect their orbital parameters to be randomly distributed if they occurred by chance, their orbital orientations with respect to the Sun are clustered extremely narrowly: with less than a 1-in-10,000 chance of such an effect appearing randomly.

Whenever we see a new phenomenon with a surprisingly non-random appearance, our scientific intuition calls out for a physical explanation. Astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown provided a compelling possibility earlier this year: perhaps a massive perturbing body very distant from the Sun provided the gravitational "kick" to hurl these objects towards the Sun. A single addition to the Solar System would explain the orbits of all of these long-period TNOs, a planet about 10 times the mass of Earth approximately 200 A.U. from the Sun, referred to as Planet Nine. More Sedna-like TNOs with similarly aligned orbits are predicted, and since January of 2016, another was found, with its orbit aligning perfectly with these predictions.

Ten meter class telescopes like Keck and Subaru, plus NASA's NEOWISE mission, are currently searching for this hypothetical, massive world. If it exists, it invites the question of its origin: did it form along with our Solar System, or was it captured from another star's vicinity much more recently? Regardless, if Batygin and Brown are right and this object is real, our Solar System may contain a super-Earth after all.

Image: A possible super-Earth/mini-Neptune world hundreds of times more distant than Earth is from the Sun. Image credit: R. Hurt / Caltech (IPAC)

We'll have all kinds of goodies to eat and drink, of course, and lots of good company and conversation, of course, but the big news is all about who we've got speaking: Babak Tafreshi, the creator of "The World At Night," will discuss his work and present a stunning program of his unique astrophotographs. Babak is an internationally known photographer and a tireless advocate for astronomy and the preservation of dark skies.

We'll have all kinds of goodies to eat and drink, of course, and lots of good company and conversation, of course, but the big news is all about who we've got speaking: Babak Tafreshi, the creator of "The World At Night," will discuss his work and present a stunning program of his unique astrophotographs. Babak is an internationally known photographer and a tireless advocate for astronomy and the preservation of dark skies.