Skyward

October 2019: California and the Universe

Since early in the last century, astronomers dreamed of the clear sky over California as a place to unlock our imaginations and study the universe. In 1917, the 100-inch Hooker telescope was opened to the poetry of Alfred Noyes, who wrote:

Since early in the last century, astronomers dreamed of the clear sky over California as a place to unlock our imaginations and study the universe. In 1917, the 100-inch Hooker telescope was opened to the poetry of Alfred Noyes, who wrote:

We creep to power by inches. …Even to- night

Our own old sixty has its work to do;

And now our hundred-inch: I hardly dare

To think what this new muzzle of ours may find.

And just think what the niog telescope did find; among many other things, it revealed that our Universe was double the size we thought it was. Despite the fact that I have visited Mount Wilson many times, my most recent visit in September gave me an insight I hadn’t experienced before. I was a guest of Scott Roberts, whose Explore Scientific telescope company had organized an observing party there. The place literally oozes history through every stone, piece of wood, and gear revealing the progress of our understanding of the Universe as it increased during the 112 years since the observatory’s founding in 1907.

During my visit there I felt as though I was standing next to some of these great astronomers, now long gone. I was standing next to George Ellery Hale as he struggled to build the Snow solar telescope, the mighty 60-inch, and the 100-inch Hooker telescope. I was standing next to Fritz Zwicky as he used the 100-inch on so many nights. Zwicky had quite the reputation as a curmudgeon. He might have included me among the many colleagues he called “spherical bastards” – meaning a bastard no matter which angle or prism you choose to look through.

I was standing next to Walter Baade. There is a story that, at the outbreak of the second world war, he was declared an enemy alien and ordered to stay near his Pasadena home. Since he, or someone, allowed the vicinity of Pasadena to include Mount Wilson, Baade essentually enjoyed three years of uninterrupted observing time on the 100-inch. With Los Angeles under occasional blackout conditions that darkened the Mount Wilson sky still further, Baade made his crucial observations of individual variable stars in the Andromeda Galaxy that he, and Bart Bok, later used to determine the size and shape of our own Milky Way Galaxy.

was declared an enemy alien and ordered to stay near his Pasadena home. Since he, or someone, allowed the vicinity of Pasadena to include Mount Wilson, Baade essentually enjoyed three years of uninterrupted observing time on the 100-inch. With Los Angeles under occasional blackout conditions that darkened the Mount Wilson sky still further, Baade made his crucial observations of individual variable stars in the Andromeda Galaxy that he, and Bart Bok, later used to determine the size and shape of our own Milky Way Galaxy.

George Ellery Hale was unsatisfied with the size and abilities of the big 100-inch telescope, and he longed for a much larger one. He hired Russell Porter, the amateur astronomer who had founded the Stellafane telescope makers meeting in 1925, to work on a 300-inch telescope. When that was deemed impractical, a 200-inch telescope was built instead. Porter’s drawings of the 200-inch were stupendous. Realizing that the 100 was unable to reach the north celestial pole due to its English double yoke mount design, he envisaged a beasutiful and elegant horseshoe design so that the 200-inch could point right at the pole if needed. Even the lowly 18-inch Schmidt camera telescope, the first telescope at Paliomar, made history as the instrument Zwicky uased to discover 100 supernovae in distant galaxies, and, near the end of its useful life, it was the telescope used in the discovery of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.

I close with a variation of a quotation by Sir Kenneth Clark. What defines the great observatories that look to the stars and revolutionize our understanding of them? I don’t know. But I know them when I see them. And the observatories at Mounts Wilson and Palomar are them.

Images: Figure 1: The venerable hundred inch telescope points toward the zenith inside its enormous dome at Mount Wilson. Figure 2: This Seth Nicholson dome once housed the 12-inch Schmidt camera that now resides at Jarnac Observatory. Both photographs by Doveed.

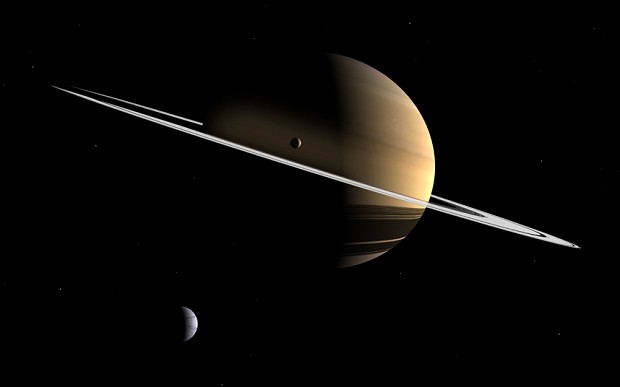

Our speaker for the Friday, June 14 GAAC meeting will be none other than Steve O'Meara, the amateur astronomer who, very unexpectedly, observed "spokes" in Saturn's ring system in 1976. Steve reported observing these phenomena with the 9 inch refractor at Harvard (an interesting account of the reception of O'Meara's observations is available

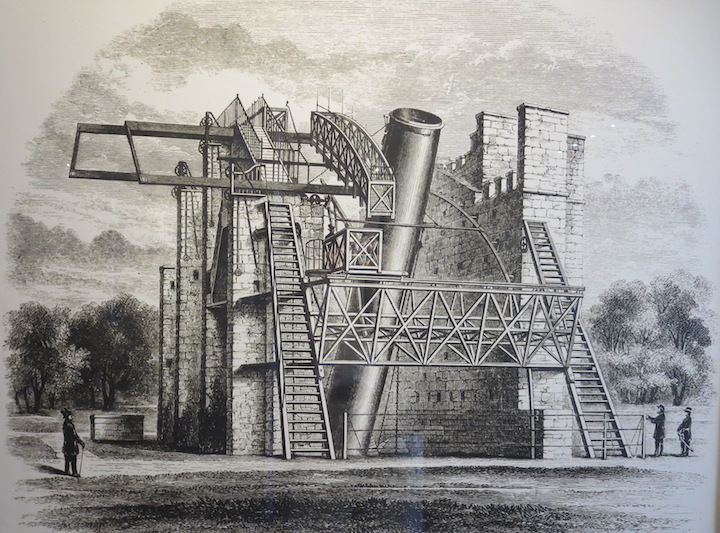

Our speaker for the Friday, June 14 GAAC meeting will be none other than Steve O'Meara, the amateur astronomer who, very unexpectedly, observed "spokes" in Saturn's ring system in 1976. Steve reported observing these phenomena with the 9 inch refractor at Harvard (an interesting account of the reception of O'Meara's observations is available  At our May 10 meeting, Amateur astronomer and perennial GAAC favorite Dwight Lanpher will speak about his visit last September to Birr Castle, County Offaly, Ireland to examine "the Great Telescope." Any review of the history of astronomy will likely discover this large telescope called the "Leviathan of Parsonsonstown." Built in Ireland in 1845 by the 3rd Earl of Rosse, it was the largest telescope in the world for 70 years. Each of two 72" speculum-metal mirrors were alternately mounted in a 54' long tube, suspended between two purpose built castle walls.

At our May 10 meeting, Amateur astronomer and perennial GAAC favorite Dwight Lanpher will speak about his visit last September to Birr Castle, County Offaly, Ireland to examine "the Great Telescope." Any review of the history of astronomy will likely discover this large telescope called the "Leviathan of Parsonsonstown." Built in Ireland in 1845 by the 3rd Earl of Rosse, it was the largest telescope in the world for 70 years. Each of two 72" speculum-metal mirrors were alternately mounted in a 54' long tube, suspended between two purpose built castle walls. During our monthly star nights at our neighborhood Corona Foothills Middle School, I sit down on a chair near the telescope to assist with the observing. The students attending are well behaved no matter their level of interest. Some of the kids are there just for the evening’s assignment. But occasionally one student or two will sit down next to me and ask me a few questions.

During our monthly star nights at our neighborhood Corona Foothills Middle School, I sit down on a chair near the telescope to assist with the observing. The students attending are well behaved no matter their level of interest. Some of the kids are there just for the evening’s assignment. But occasionally one student or two will sit down next to me and ask me a few questions.