David H. Levy

Daffy Duck

Agreed, this seems like an awfully daffy title for an astronomy article. But there is method to the madness, and there is a story. During the late summer of 2019 there was a star party in southeast Arizona that featured a dark sky and five perfect back-to-back nights As I spent hour after hour hunting for comets, I came across the sprawling North America Nebula in the northern sky constellation of Cygnus the swan. But this time something different appeared. It was a strange structure, the outline of a dark nebula bordered by a slightly brighter cloud. The whole feature was rather subtle, so that sometimes it was there, and then it faded so that sometimes it wasn’t. I spent some time trying to determine a name for it. It looked like the head of a duck. I couldn’t call it the wild duck nebula, as there is a cluster with that name. And Donald Duck is a bit confusing. So how about calling it the Daffy Duck nebula?

Agreed, this seems like an awfully daffy title for an astronomy article. But there is method to the madness, and there is a story. During the late summer of 2019 there was a star party in southeast Arizona that featured a dark sky and five perfect back-to-back nights As I spent hour after hour hunting for comets, I came across the sprawling North America Nebula in the northern sky constellation of Cygnus the swan. But this time something different appeared. It was a strange structure, the outline of a dark nebula bordered by a slightly brighter cloud. The whole feature was rather subtle, so that sometimes it was there, and then it faded so that sometimes it wasn’t. I spent some time trying to determine a name for it. It looked like the head of a duck. I couldn’t call it the wild duck nebula, as there is a cluster with that name. And Donald Duck is a bit confusing. So how about calling it the Daffy Duck nebula?

Thus, the structure is named after Daffy Duck. It is No. 403 in my catalog of interesting things found during my more than 56 years of comet hunting. I believe it is a small dark construction at the northern tip of the North America Nebula, about where Hudson Bay is not accurately located. It could have been where the Gulf of Mexico is, but that area is virtually impossible to spot visually, even under a dark sky. Like the Horsehead Nebula in Orion, it is very difficult to spot and it is best viewed only in a photograph. The accompanying picture shows it at its top, a little to the left of center. The accompanying photograph was taken using the Hubble Space Telescope.

There are more than four hundred other celestial objects that have come my way over the years. Beginning with NGC 1931 which I spotted in January 1966, many of these are already well-known deep sky objects in the night. But a few are interesting groupings of stars, called asterisms, that no one has pointed out before. One of my favorites is a structure of faint stars I call “Wendee’s Ring.”

These always welcome objects in the sky are fun to observe and they enhance my enjoyment of my hours under the stars. When I can see Daffy Duck, it reminds me of the happy hours I spent as a child at Beaver Lake, an artificial pond near the top of Mt. Royal in Montreal, that hosts dozens of mallard ducks. On clear, moonless nights now, I offer a cosmic hello to Daffy Duck and the many objects in the night sky I have come to treasure as good friends.

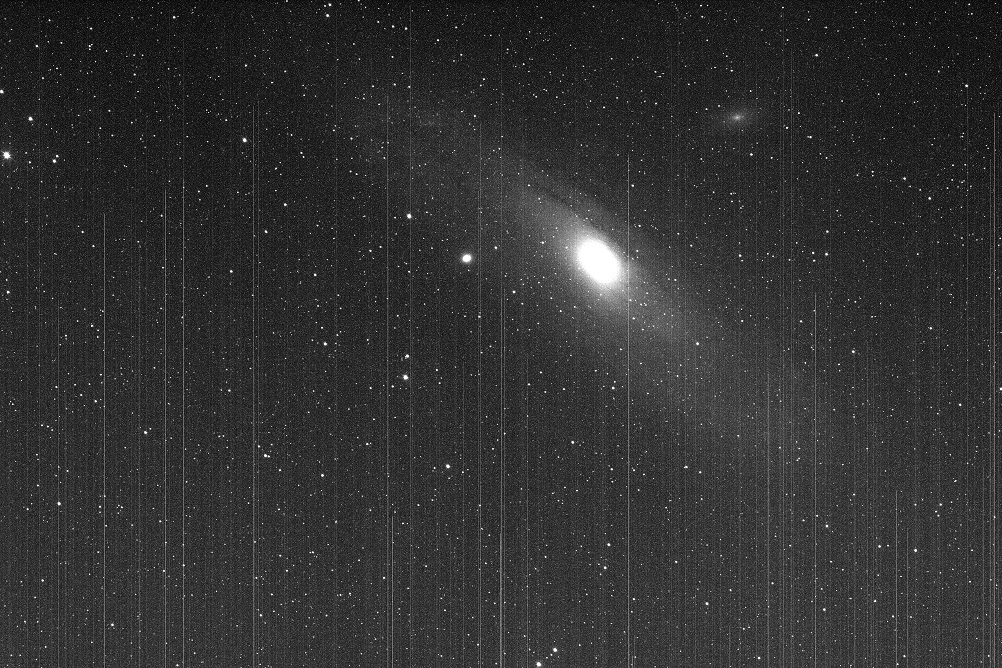

A few weeks ago, I received a message from Cameron Gillis, an amateur astronomer who wrote that he liked galaxies. Just for fun, I decided to take the opposite approach, a philosophical reversal. If he likes galaxies, then I hate them. As we prepared for our meeting I began to explain the various reasons why I hate them. When, for example, I am observing with a telescope and the Andromeda galaxy enters my field of view, I quickly leave the telescope and ride my bicycle to the end of our driveway and back. The more I stretch the story the greater the laughter becomes. I especially get annoyed by the dark Hydrogen-II regions that stretch across its hideous girth. The cluster of galaxies in the Virgo cluster, particularly Messiers 84 and 86, are so bland that I sometimes have to leave the telescope altogether!

A few weeks ago, I received a message from Cameron Gillis, an amateur astronomer who wrote that he liked galaxies. Just for fun, I decided to take the opposite approach, a philosophical reversal. If he likes galaxies, then I hate them. As we prepared for our meeting I began to explain the various reasons why I hate them. When, for example, I am observing with a telescope and the Andromeda galaxy enters my field of view, I quickly leave the telescope and ride my bicycle to the end of our driveway and back. The more I stretch the story the greater the laughter becomes. I especially get annoyed by the dark Hydrogen-II regions that stretch across its hideous girth. The cluster of galaxies in the Virgo cluster, particularly Messiers 84 and 86, are so bland that I sometimes have to leave the telescope altogether!  Observing the universe relies to a great degree on our ability to model starlight, and thereby predict underlying stellar properties, such as mass and chemical composition.

Observing the universe relies to a great degree on our ability to model starlight, and thereby predict underlying stellar properties, such as mass and chemical composition.

In the words of this beautiful Christmas carol,written during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, we are reminded of Christmas, the biblical Book of Matthew, and the Star of Bethlehem. Famous as it is, this story appears but once in the Gospel according to Matthew::

In the words of this beautiful Christmas carol,written during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, we are reminded of Christmas, the biblical Book of Matthew, and the Star of Bethlehem. Famous as it is, this story appears but once in the Gospel according to Matthew::

On Friday night, December 13, for our 16th annual Holiday Party, we are fortunate to once again have with us the celebrated Kelly Beatty, Senior Editor of Sky & Telescope Magazine (see more of Kelley's bio below). This year Kelly's presentation asks the perennial question "Are We Alone?

On Friday night, December 13, for our 16th annual Holiday Party, we are fortunate to once again have with us the celebrated Kelly Beatty, Senior Editor of Sky & Telescope Magazine (see more of Kelley's bio below). This year Kelly's presentation asks the perennial question "Are We Alone?